words by Millie Harris | photo by Heidi Kewin

When a photograph of Lea Ypi’s grandmother, Leman, was posted on social media by a total stranger, she becomes determined to discover who her grandmother truly was, an endeavour that sounds simple in theory. However, Indignity: A Life Reimagined is not a simple story. Best known for her memoir Free, which traced her own coming of age in late communist and post-communist Albania, Ypi returns with Indignity to ask quite similar questions, but from a completely different angle. Instead of narrating her own childhood, the author presents herself as a character in a third person perspective and turns to the life of her grandmother. The novel asks, who gets to answer the question of who someone is? One’s family, the government, or the person who lived the life themselves? Ypi attempts to gather as much information as she possibly can and, from this point onwards, she reimagines her grandmother's life through documents and her own imagination, attempting to re-create the life she lived.

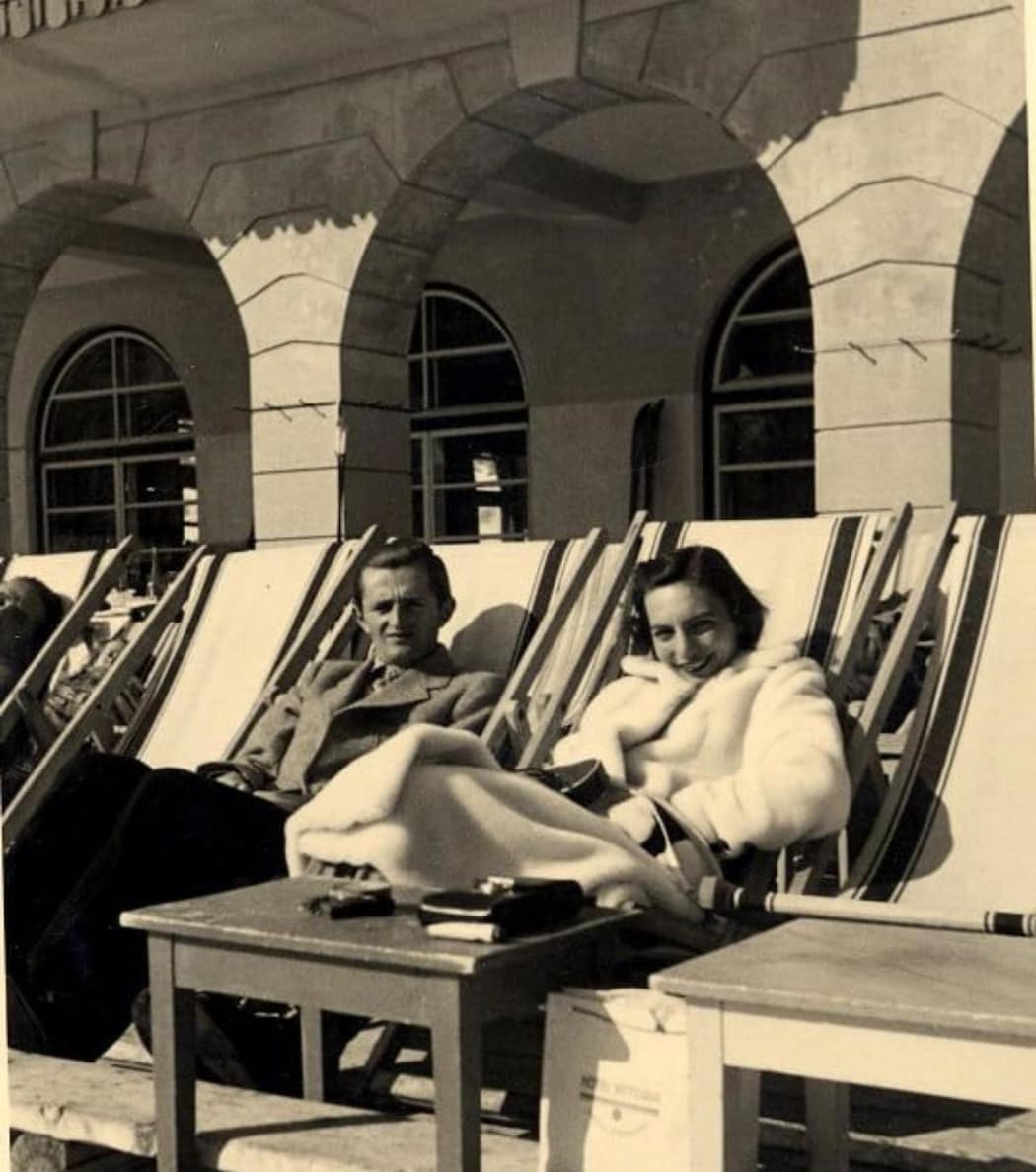

The photo in question. Lea Ypi found this photo while scrolling on social media. The photo shows Asllan Ypi and Leman Leskoviku on their honeymoon, 1941. Photo: Allen Lane

Personally, I have a love/hate relationship with historical fiction. It’s such a difficult genre to successfully accomplish and I find myself either utterly enthralled by what I’m reading, or, on the flip side, utterly bored. However, the opening chapter drew me in quickly. I found some of the set up a little too expositional and repetitive, but the underlying concept of returning to such a personal story through the lens of both archives and memory instantly had me engaged. However, rather abruptly, the book’s voice shifts just as I found myself invested in what was being offered to me as a reader. After that, I struggled to find my footing again. The tone of the fictionalised sections felt quite different from the opening and, for a while, I didn’t feel particularly invested in either the characters or the emerging storyline. That, however, changed again when another shift in the novel gave it a renewed sense of urgency and emotional weight. From that point onwards, the reconstruction of Leman Ypi’s world came into focus for me. I began to care far more about how she navigated the world around her and how the effects of what she has lived through shaped the rest of her life.

One of the most striking aspects of Indignity is how clearly it illustrates the complexity of twentieth-century politics and identity in the Balkans and beyond. Leman, the writer’s/protagonist’s grandmother, is ethnically Albanian, but she was born and raised in Salonica (Thessaloniki) when it was still part of the Ottoman Empire, before it became Greek in 1912. She had never visited Albania until the Second World War, when the Nazi occupation of Greece pushed her to cross the border. There, she met Asllan and eventually spent the rest of her life in a country that is technically ‘hers’, but also is not. The novel moves through invasions by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, then into Albania under Enver Hoxha’s harsh, isolationist socialist dictatorship. Across each shift in regime, it traces how borders and labels change around people who are simply trying to live. These (hi)stories undermine any simplistic idea of who ‘belongs’ where, and really makes the hybrid form of the book feel necessary, as it reflects the instability of Leman’s own position where she is never entirely at home in any country or language. This is a novel that is part memoir, part imaginative reconstruction and part archival investigation… None of these, on their own, could capture how thoroughly politics and geography shape individuals' lives. The fact that this is a hybrid form novel is not only incredibly interesting, but absolutely necessary to truly understand the impact had upon Leman’s life.

At the same time, this is also where some of my reservations lie. The fictionalised sections which make up most of the book are certainly well written but, as a novel, it didn’t quite reach far enough for me. The narrative structure felt more like a life unfolded in sequence, set against major historical events, rather than shaped into something with a strong dramatic structure. In this book there is a great deal of ground to cover and, at times, it feels rushed. We move relatively quickly through different eras, especially the later sections under Communism, which feel comparatively thin to the earlier sections. Those later chapters focus more on the machinery of the state with detail on archived files and speculation about informers rather than on Leman’s personal life. I found myself wanting more detail about how the character endured the long imprisonment of her husband or how she experienced the transition into the post-communist period. These topics are subtly touched on but, as a reader, I desired more about Leman herself.

What kept me reading, beyond the historical material, was Lea Ypi’s brilliant prose. There is something unusual about the style that, at times, reminded me faintly of The Picture of Dorian Grey in that events unfold, but are frequently paired with philosophical reflections. For example, this line in particular fragment stood out for me:

“There is something about the human spirit, my grandmother would say, that withstands all attempts at offence, injury or humiliation — something animals are incapable of because they are incapable of thoughts disconnected from their immediate existence. We call it dignity.” (Ypi, 14)

Given the book’s title, Indignity, this line has an ironic edge to it, especially given how early on we read this in the novel. If dignity is the small surplus of the self that survives “offence” (14) and “humiliation” (14), then indignity is the attempt to prove that surplus doesn’t exist at all. It is history itself insisting that everything in a person could be counted and then broken by their command. In that light, the grandmother’s remark is saying, in effect, that there is a point beyond which power cannot reach, even when it has taken almost everything else. But so much of Indignity takes place through files and reports, in all the places where a life is translated into categories and paragraphs, and we are shown here just how thoroughly a person can be described on paper and how little that description actually contains. Bureaucracy seems excellent at keeping records of names and terrible at recognising them as people. Against that, Ypi’s grandmother says that however complete the archive may look, there is always a part of people that withstands the humiliation documented and refuses to fit into that box: the so loved ‘indomitable human spirit’.

This line, amongst many, also stopped me in my tracks:

“We need to believe that such a man is tormented by his own nature, in order to tolerate the fact that this nature makes others suffer so.” (Ypi, 55)

It is a sharp little sentence that yet again shows how we reimagine the lives of those around us for any given reason. In this case, how we can turn perpetrators into tragic figures so that the world feels fractionally fairer, or at least less unbearable. These moments of philosophical musings are where Ypi’s style feels most distinct. They are reflective without becoming too abstract whilst also helping to connect personal experience to larger ethical and political questions in a way that suits the subject matter. I caught myself stopping more often over these small passages than at the plot itself.

Structurally, the introductory sections to each of the three parts, written from Ypi’s own perspective, are what hold the book together. In these chapters she steps back from Leman’s reconstructed life to think through what she has discovered so far, how the archives either complicate or confirm the family stories she knows, and how to make sense of both incomplete and contradictory evidence. These sections were, for me, the most engaging. They give us access to her doubts and the ethical questions raised by writing about someone else’s life. I would happily have read more of this.

Despite my reservations on the hybrid structure and the occasional feeling of narrative thinness, Indignity stayed with me. It is a thoughtful, carefully constructed work that offers a story of a woman whose life was shaped by the forces of her time, without reducing her to a symbol. For me, this is a solid four star book. I didn’t love it as much as I expected to, largely because the formal experiment doesn’t quite land on the novelistic side, but I admired it a great deal. Readers will likely find a lot here to think about.